CCW’s review of water companies’ 2025-30 business plans

A report to Ofwat

The Consumer Council for Water (CCW) is the statutory consumer organisation representing household and non-household water and sewerage consumers in England and Wales.

Because customers cannot choose their water provider, it’s especially important that their voice is heard in how the sector delivers their services and protects the environment.

CCW is an integral part of the five-yearly Price Review process. We scrutinise water companies’ business plans to make sure the customer voice is heard at every stage of the process.

Since these plans were published, at the beginning of October 2023, our teams have been going through them in detail. This work includes assessing service improvements, investment and affordability support.

We have assessed plans to see how well they reflect evidence of customers’ expectations and priorities, and whether they adequately address areas where some companies are currently performing poorly. The business plan should also show how it is a five-year milestone in a longer-term strategy.

The context for this price settlement for the water sector is a cost-of-living crisis, a changing climate and a strong focus on the environment. So consumers need to see the outcome from PR24 as being affordable, sustainable, and delivering a noticeable change in service or environmental protection.

This overview document provides CCW’s views on issues that feature in all or most of the companies’ plans.

We have also produced specific detailed assessments of each company’s plans, which we have shared with them and discussed their priorities and the trade-offs they have made.

Our key recommendations for Ofwat ahead of its draft determinations

- CCW wants to see all the water companies doing everything they can to eliminate water poverty. Via Water UK, the water companies (except Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water) have all made a Public Interest Commitment (pdf) to make bills affordable for all households with water bills more than 5% of their disposable income by 2030. Ofwat should require all the water companies which are not committing to end water poverty to offer greater financial support to their customers in the draft determinations. Ofwat should place a regulatory commitment on companies to use a proportion of future outperformance to fund affordability assistance.

- The PR24 investment programme is massive. But it must be deliverable and it must get delivered. Customers must see tangible improvements for their money. If they don’t, trust in the water sector – already at a 12-year low – will fall even further. Ofwat must require companies to explain to the people they serve what actual benefits they or the environment will get in return for increases in their bills.

- Ofwat should favourably consider companies who clearly demonstrate that their stakeholders have scrutinised and challenged their customer engagement plans effectively and can show how customer views have been used to form their plan. Likewise, Ofwat should scrutinise companies who have isolated stakeholders and/or only selectively used customer views to justify plans that were already set.

- CCW understands that water companies need to spread investment over a longer term to prevent further bill increases. It is important that any deferment of investment as a result of these trade-offs does not lead to a risk in service quality for customers or have a negative impact on the wider environment.

- CCW wants Ofwat to set companies challenging performance commitment targets for 2025-30 that reflect customers’ expectations for improvements and make poor performers improve. Performance commitment targets must also reflect where bill payers’ money is being spent – in some business plans, the high level of investment proposed does not translate into ambitious targets in those areas of service.

- Customers will see a big increase in their water bills and would not like their hard-earned cash taken off them if it is unlikely to be spent as planned, or to pay for investment or operational improvements that were funded in the past. Consumers must be assured that they are not being asked to pay twice and that there are strong protections in place to return their money to them in the event of failure to deliver.

- We all need plentiful supplies of water. But this is at risk because climate change is already putting strain on the country’s water resources. Ofwat must make companies demonstrate how behaviour change forms part of their strategies to ensure supplies are resilient for us all, now and in the future.

- From CCW’s consumer research, we know that customers do support the use of nature in managing water – and they are happy to pay extra for it. Yet nature-based solutions have been taken out of many PR24 plans in favour of building concrete tanks. Ofwat should scrutinise the reasons behind the companies’ choices about how they plan to reduce the number of storm overflow spills.

- Ofwat should hold water companies to account for the commitment they made on achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2030 (pdf).

- Customers should not have to pay higher costs due to inefficient financial decisions a company made in the past.

Overview of CCW’s assessments

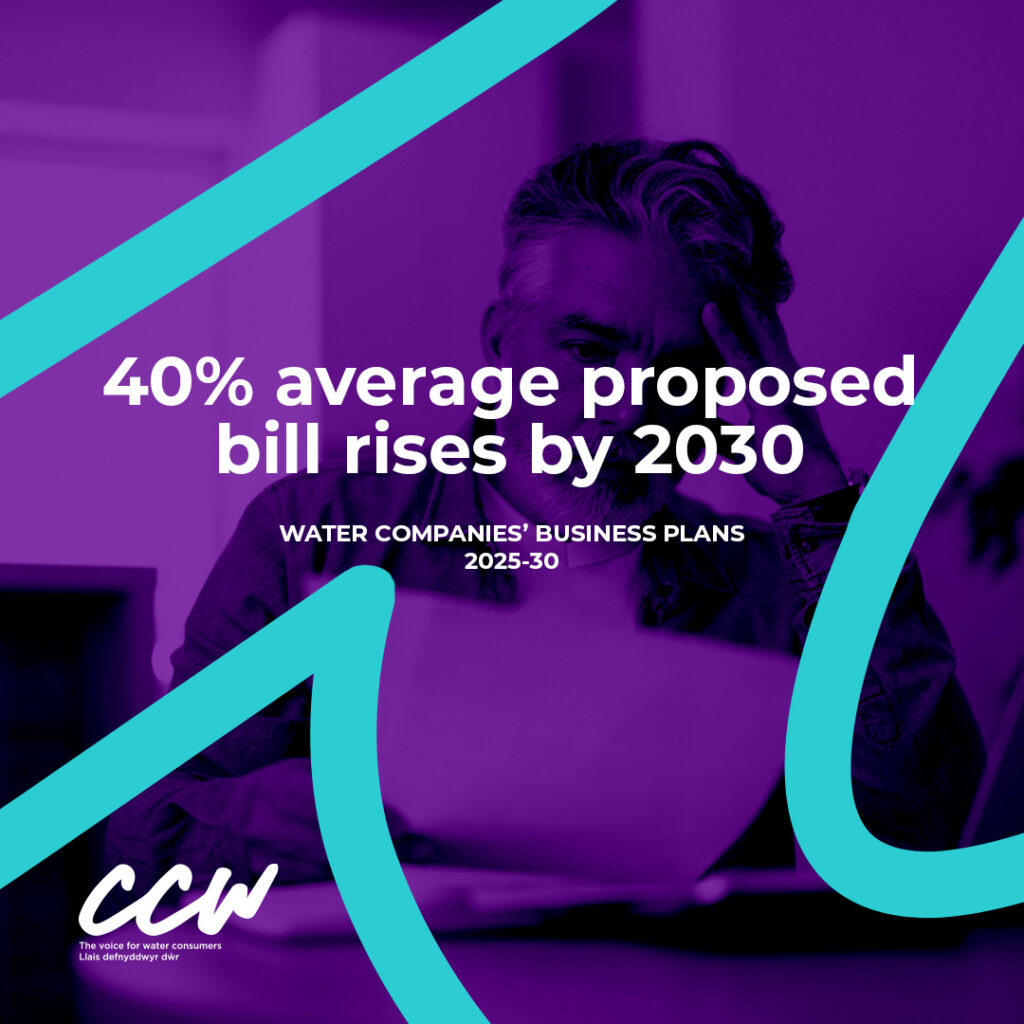

Under PR24, water companies are proposing considerable bill increases. The average rise is 40% after inflation[1]. The highest planned increases are Southern Water (70%) and Thames Water (56%) once inflation is added. Both these companies are currently performing poorly against targets for delivery of water and wastewater services.

All the companies have tested the acceptability to their customers of these business plans. Their research shows that consumers do recognise the need for investment – overall, an average of 68% of customers support the stated outcomes of the companies’ plans. But they expect to see companies addressing high-profile areas of poor performance, particularly the reliability and resilience of services, and protecting the environment.

Some companies (Yorkshire Water, Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water and Hafren Dyfrdwy) propose to load more of the bill increases into the first year of the price control period (ie 2025). In Yorkshire Water’s case, customers did support this bill profile when they were asked. Some of the water companies have told CCW that their proposed year-one increases are to increase revenue to ease what they see as financeability risks. CCW’s view is that if customers’ bills increase, they need to see what they are getting in return for their money.

Given that cost-of-living pressures are likely to still be high in 2025, Ofwat should consider smoothing out the impact of the bill increases to help customers’ budgets.

Any spikes early on in the five-year period need to be fully justified. Water companies must demonstrate to Ofwat that they need the money upfront rather than have it spread over the five years 2025-2030. They must also prove that they are prepared to spend that money as quickly as possible after it’s taken from bill payers. Money should not be sitting in water companies’ accounts if they’re not in a position to invest it quickly.

[1] Based on a forecast of CPI-H inflation of 2%pa. Before inflation the average increase is 26%. The weighted average before inflation is 31% for water and wastewater companies and 15% for water-only companies.

As part of PR24 water companies tested their business plans among customers for acceptability and affordability. All but one used prescriptive guidance set by CCW and Ofwat. This means results from different companies are directly comparable.

The results show that while there was, on average, 68% acceptance of what companies propose to deliver, the average level of customers who say they can afford the bill increase was very low at 16%.

The majority of people said that their bill is either unaffordable now; will be in the future; or they don’t know if they will be able to afford it.

According to the National Institute for Economic and Social Research, falling real wages and rising bills and debt levels have hit households in the bottom half of the income distribution hardest, leading to a shortfall in their real disposable incomes by up to 17% over the period 2019-2024.

So increased bills will hit customers harder in 2025-2030 than they would have done in previous price reviews. It is paramount that customers see tangible improvements for their money. If they don’t, trust in the water sector – which is already at a 12-year low – will be further eroded.

Ending water poverty

CCW wants to see all the water companies doing everything they can to eliminate water poverty. Via Water UK, the water companies (except for Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water) made a Public Interest Commitment (pdf) to make bills affordable for all households with water bills more than 5% of their disposable income by 2030.

There is a wide gap between the large proposed bill increases in PR24 and the small percentage (16%) of customers who say they can afford them. Companies face a big challenge in helping customers who struggle to pay their water bills, now or in the future.

Many companies highlight increases in the total number of people they’re helping. Yet very few water companies are aiming to eliminate water poverty through PR24. For example, Hafren Dyfrdwy will increase the number of customers receiving some form of support from 3.7% of customers in 2022-23 to 8.2% by 2030. However, 12% of their customers are currently estimated to be living in water poverty.

CCW warmly welcomes the commitments from the companies aiming to eliminate water poverty under PR24 – Severn Trent, Wessex Water, Northumbrian Water (with Essex and Suffolk) and the Pennon group of companies.

Ofwat should require the companies not committing to end water poverty to offer greater support in the draft determinations.

Ending water poverty is only part of the picture. Many people who are currently just about managing will need help to make sure they don’t slip into water poverty. CCW wants Ofwat to encourage companies to provide a wide range of support measures to ensure people in need get support when they need it.

Company funding for those struggling to pay

CCW is encouraged to see some companies using funds from their own investors, shareholders or parent companies to support customers struggling to pay their bills using a range of affordability support measures – United Utilities, Dŵr Cymru, Yorkshire Water and SES.

In addition to its voluntary contribution, Yorkshire Water has committed to use a proportion of its future outperformance to eradicate water poverty.

CCW would like to see all companies making such commitments.

Ofwat should place a regulatory commitment on companies to use a proportion of future outperformance to fund affordability assistance.

Customer funding for social tariffs

CCW is pleased that many water companies[2] have secured agreement from their customers to increase their social tariff for PR24. However, some water companies’ customers haven’t agreed to support an increase in the in-company cross subsidy – eg South Staffordshire and Cambridge Water.

A single social tariff would end water poverty by providing a single funding pot that would offer guarantee financial support across England and Wales.

[2] Anglian Water, Hafren Dyfrdwy, Northumbrian Water, Severn Trent, South East Water, Southern Water, South Staffs and Cambridge Water, Thames Water, United Utilities, Wessex Water, Bristol Water, Bournemouth Water, Yorkshire Water, Portsmouth Water

CCW agrees that sewage pollution must be reduced. Companies must successfully deliver their environment programmes to meet consumers’ expectations and so increase trust in the sector.

Much of the 63% increase in proposed expenditure for PR24 (compared to the 2019 final determinations)[3] is required by legislation. The Water Industry National Environment Programme for England (WINEP) and the National Environment Programme for Wales (NEP) are significantly higher than equivalent programmes in previous price controls, reflecting new UK and Wales legislation.

There will be a particularly large increase – £9 billion of the overall £95 billion proposed total expenditure across all plans – in work to deal with storm overflow spills.

Companies’ consumer research did broadly show that customers do want to see the outcomes that the WINEP and NEP should deliver. An average of 68% of customers find the PR24 plans acceptable.

But the WINEP/NEP must actually be deliverable – and get delivered. It must lead to tangible environmental improvements that customers can see or experience.

CCW questions the deliverability of some of the larger programmes proposed in PR24. Some water companies have not managed to deliver the programmes they committed to in PR19 – most notably, Southern Water and Thames Water.

CCW is also disappointed to see that nature-based solutions have been taken out or reduced in some water companies’ plans in favour of building hard asset-based solutions. It’s quicker to produce concrete tanks than it is to design and install sustainable drainage solutions or partnership-based catchment management. Yet these nature-based solutions improve the environment and reduce the pressure on treatment processes.

We know some companies – South West Water, Affinity Water, Northumbrian Water and Wessex Water – have successfully used nature-based solutions. Some companies engage well with the Environment Agency or Natural Resources Wales to identify where nature-based solutions can be used.

However, the interpretation of the UK and Welsh governments’ strategic priorities for Ofwat could undermine the use of catchment-wide, nature-based solutions and sustainable drainage schemes. Companies seeking to quickly go beyond the proposed annual average target of 20 spills per storm overflow may be deterred from using more sustainable, but longer-term or more uncertain, solutions.

From CCW’s consumer research, we know that customers do support the use of nature-based solutions – and they are willing to pay extra for it, and for it to take a longer to deliver the outcome. So it is a shame that target-hitting could be put in conflict with supporting the wider environment. This does nothing to increase trust in wastewater companies. Fewer than half of people in England and Wales currently trust them to protect the environment.

Ofwat should scrutinise the reasons behind the companies’ choices on how they plan to reduce the number of storm overflow spills and address other sources of pollution to make sure they are getting the best long-term solution for the customer and the environment.

[3] £54605m totex allowed for in 2019 Final Determinations, £90189m totex proposed in PR24 business plans.

Several water companies have deferred some of the investment they had planned to use to improve the resilience of their infrastructure. Instead, they have put that money into the large WINEP/NEP environment investment demanded by the legislation.

Similarly, some investment earmarked for meeting Water UK’s Public Interest Commitment (pdf) for the companies to achieve net zero carbon emissions for the sector by 2030 has been dropped to accommodate the WINEP/NEP requirements.

From talking to the water companies about their plans, we know that they have made several trade-offs in their investment choices in order to accommodate the WINEP/NEP.

While we accept that companies need to spread investment over a longer term to prevent further bill increases, it is important that any deferment of investment as a result of these trade-offs does not lead to a risk in service quality for customers or have a negative impact on the wider environment.

The Climate Change Committee is clear in its Sixth Carbon Budget that front-loading carbon reduction reduces the cost and is the most effective way to minimise the UK’s carbon emissions in order to meet the Paris goals.

Where companies are deferring investment to replace assets such as lead pipes, mains or upgrade treatment works, CCW is concerned that this may increase the risk to service delivery. Addressing these issues after 2030 may cost more – leading to an increase in bills for customers who could have got the same result more cheaply five years earlier.

PR24 includes many plans to roll out smart meters, especially in areas of higher water scarcity. CCW supports smart metering because it gives water companies and customers data to identify leaks and water usage patterns – which can be used to change consumers’ behaviour to reduce demand.

A sector in which public trust is at a 12-year low needs to keep its promises.

CCW has concerns about some companies’ ability to deliver the large programmes of work they are planning for PR24. In the current price control period (PR19), we already see companies struggling to meet their commitments – and this is with much smaller programmes of work.

Thames Water and Southern Water are currently performing poorly on several key metrics that are important to customers. So delivering the scale of improvement in their plans over the 2025-30 period seems to us to be extremely challenging.

Customers will see a big increase in their water bills and would not like their hard-earned cash taken off them if it is unlikely to be spent as planned. Consumers will need assurance that strong enough protections are in place to stop that happening.

Consumers may be concerned that a large investment is needed just to ‘catch up’ on asset resilience, especially for Thames Water. They may question why costs permitted in previous price controls have not delivered the required resilience improvements.

Customers must not pay twice. Ofwat needs to assure customers that any 2025-30 allowances do not include schemes to address asset resilience that should have been delivered under earlier cost allowances.

Ofwat’s incentives should drive companies to deliver their commitments to customers and the environment. If companies fail to do this, they must return that money to consumers.

Several companies ask for lower Outcome Delivery Incentive (ODI) penalty and reward rates than those set by Ofwat. Some say the rates do not reflect their customers’ priorities – eg Anglian Water. Some say the risk of penalties is too great because it affects their financeability – eg Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water.

Ofwat should set rates that are consistent with the figures already set so they are strong enough to drive performance improvement. This is especially important in areas where companies are currently performing poorly.

Some companies – Thames Water and Wessex Water – have diverged from Ofwat’s assumption for the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). This is unacceptable because it means the bill impacts presented in the plan are inflated to reflect a higher financing cost assumption than Ofwat has indicated is a suitably efficient WACC.

Ofwat should not be held to ransom by companies saying that they cannot deliver improvements for customers and the environment without exceptional costs being allowed that may be inefficient or unjustified.

Several plans have a range of cost adjustment claims that are for areas of operational expenses (eg power costs) that a company says are uniquely higher in their area. Ofwat should scrutinise these costs to ensure that any claim is truly exceptional.

If additional cost allowances are given in draft determinations, they should enable the company to deliver value to customers that is comparable to the costs allowed.

Ofwat should not allow higher cost allowances for companies seeking to decrease risks in the WACC, ODI rates, performance commitment targets and other financial incentives or efficiency challenges to mitigate losses caused by past structural financing choices. Customers should not have to pay higher costs due to inefficient financial decisions a company made in the past.

The starkest example of this is Thames Water, whose plan appears to be dependent on Ofwat allowing it some leeway to accommodate its perilous financial position due to high debt and uncertainty over its future equity funding.

We all want plentiful supplies of water, but this is at risk in the UK, with climate change already putting strain on water resources.

Ofwat must direct companies to be proactive in helping customers change their behaviour and reduce their water use. CCW has made a proposal for a single umbrella body – ARID – to provide overall strategy; coordinate all the demand management activities; provide funding for new demand side projects; and evaluate them via a central evidence base so future investment can be targeted at the programmes that deliver the best results.

Several companies have set strategies in PR24 to reduce leakage and invest in new water resources and smart meters. This is an essential part of the toolkit to preserve water resources for the future. But company plans are light on how companies will actually help customers change their behaviour to reduce their water use. For example, smart metering alone won’t deliver the demand reductions that are required. It must be accompanied by specific plans to exploit the data and the opportunities that smart metering brings.

Ofwat must require companies to show how behaviour change forms part of their strategies to ensure the country’s water supplies remain resilient and reliable for all.

Companies’ research shows that customers place an increasing importance on water companies reducing their carbon footprint. Companies need to be part of the multi-sector work needed to achieve net zero carbon emissions to address climate change, but the business plans show that some companies will not achieve the sector’s Public Interest Commitment to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2030.

Ofwat should hold water companies to account for that commitment they made on achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2030.

Performance commitments (PCs) track and incentivise how well companies improve their delivery of service. If targets drive improvements in consumers’ priorities, customers should see evidence of improvements in return for their bill increases.

CCW wants Ofwat to set companies challenging PC targets for 2025-30 that reflect customers’ expectations about improvements; that make current poor performers improve; and that reflect where money is being spent.

Many of the water companies offer stretching targets as part of PR24 and are aiming for the upper quartile of performance in areas that are either customer priorities or where they are currently performing comparatively poorly.

However, some companies are proposing comparatively poor targets (ie aiming for the lowest quartile by 2030) in areas of service where the company’s research shows customers expect them to improve. In these cases, Ofwat should satisfy itself in its draft determinations that those targets actually meet customers’ expectations.

In some cases, the high level of investment planned has not translated into ambitious targets in the relevant areas of service. This is particularly the case in environmental improvements, where some companies’ targets for bathing/river water quality, pollution incidents and storm overflows do not match the programmes they propose.

All companies are committing to roll out smart meters. CCW welcomes this, though this has not always translated into ambitious targets to reduce leakage, per capita consumption or business demand. Companies have made a Public Interest Commitment (pdf) to triple the rate of leakage reduction by 2030, yet not many companies will achieve this according to their plans. We would like Ofwat to increase the companies’ targets where high cost investment should be driving greater ambition.

Only two companies offer customer experience and developer experience (C-MeX and D-MeX) targets because these metrics are currently under review. Once the new metrics are set, companies must engage with CCW on their proposed targets ahead of the draft determinations. These metrics should drive improvements in the customer service experience and reduce complaints, so they should be suitably challenging, especially for the poor performers.

To underpin their plan proposals, companies have done a lot of research into the needs and expectations of different consumer groups. The credibility of the price review relies on how well companies have listened to their customers and made plans that deliver what customers want.

The introduction of centralised research – especially the prescriptive CCW/Ofwat guidance for testing plans – ensured good practice was generally followed and that results are comparable across the sector.

The introduction of the ‘Your Water Your Say’ online challenge sessions also ensured companies have been more accountable to their customers. Some companies received over a hundred questions from interested customers before, during and after the events.

However, we see variation in how well different companies engaged with their customers and then incorporated this feedback into their plans.

CCW has seen some good examples of business plans that reflected evidence from customers – Dŵr Cymru Welsh Water, Northumbrian Water and Wessex Water.

However, some companies didn’t follow CCW/Ofwat’s principles of good customer engagement. And some did not demonstrate how their customers’ views are reflected in their plan – eg South East Water.

Several companies need to be better at allowing their stakeholders to view, scrutinise and challenge how they engage with customers as they develop their business plan proposals. Some companies also need to be better at showing how customers’ views have been used to build their plans.

Ofwat should favourably consider companies who clearly demonstrate that their stakeholders have scrutinised and challenged their customer engagement plans effectively and can show how customer views have been used to form their plan. Likewise, Ofwat should scrutinise companies who have isolated stakeholders and/or only selectively used customer views to justify plans that were already set.

If companies cannot demonstrate that their proposals reflect customer evidence, Ofwat should only allow the company’s request if there is a convincing technical case for allowing such a proposal (eg evidence of risk of service failure).

There are variations in how well water companies engaged with their stakeholders in the Independent Challenge Groups (ICGs).

Some companies – eg Wessex Water, the Pennon group of companies, Severn Trent and Northumbrian Water – worked well with their ICGs, letting them scrutinise the plan’s building blocks and the customer evidence to support it. It’s clear that the ICGs’ challenges influenced the plan.

However, some ICGs were frustrated by a lack of engagement with their companies. One ICG’s influence faded in the latter stages of the business plan development as the company met them less often so opportunities to challenge were reduced – Portsmouth Water. And in one extreme case, the relationship between the company and its ICG broke down completely – South East Water.

Hafren Dyfrdwy declined to have an ICG and hired one person to act as its customer engagement expert instead. This led to reduced resource, stakeholder engagement and challenge.

If companies are not fully transparent and do not engage with their ICGs, their plans are not sufficiently scrutinised or challenged by stakeholders. This means plans are not as customer-focused as they should be. CCW is reviewing how ICGs were deployed in PR24 to identify more effective and inclusive customer engagement for future price reviews.

Companies must communicate clearly and frequently to their customers what tangible results they are getting in return for their bills going up. This could be better service delivery; recognisable improvements to the environment; and/or reductions in water poverty.

Both Ofwat – in its price determination announcements – and the companies should also show customers the potential impact of forecast inflation on bills for 2025-30, even if this can only be based on Treasury forecasts at present. If customers are shown average bills that do not reflect the impact of inflation, that is somewhat misleading.

Transparency over both the price tag and the benefits proposed at PR24 is a vital component towards rebuilding trust in the sector. People need to understand what they are paying for.

CCW supported Ofwat’s introduction of long-term adaptive planning principles in the price review methodology. We are pleased to see this has led to improved clarity in how companies have presented the long-term strategy that the five-year plan sits underneath.

Companies identified a core pathway to delivering long-term outcomes, and identified alternative paths in case different economic, political or environmental circumstances arise.

In some cases, this has shown how some areas of investment are being deferred to future price controls to accommodate shorter-term WINEP pressures.